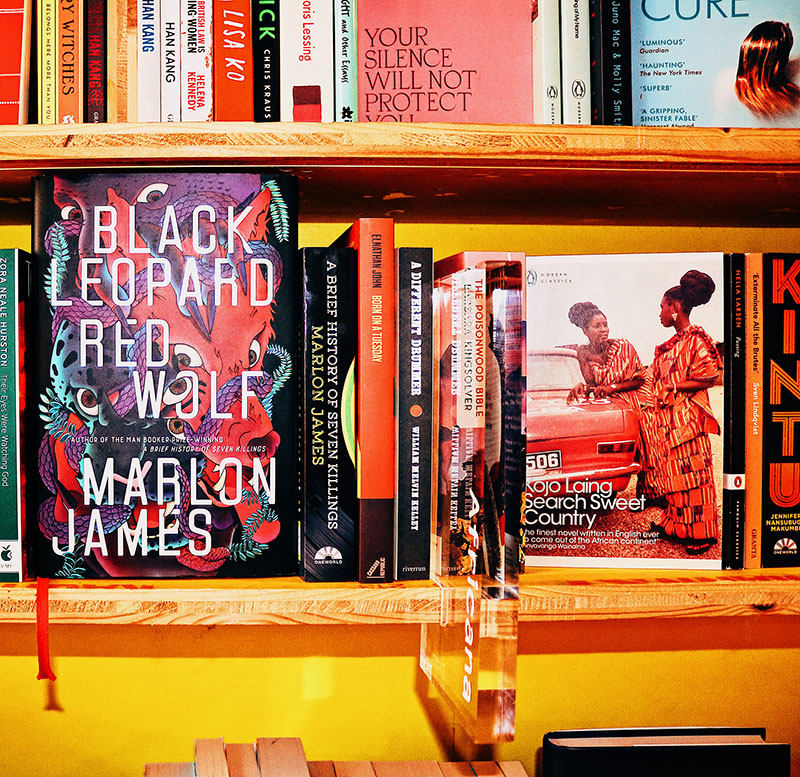

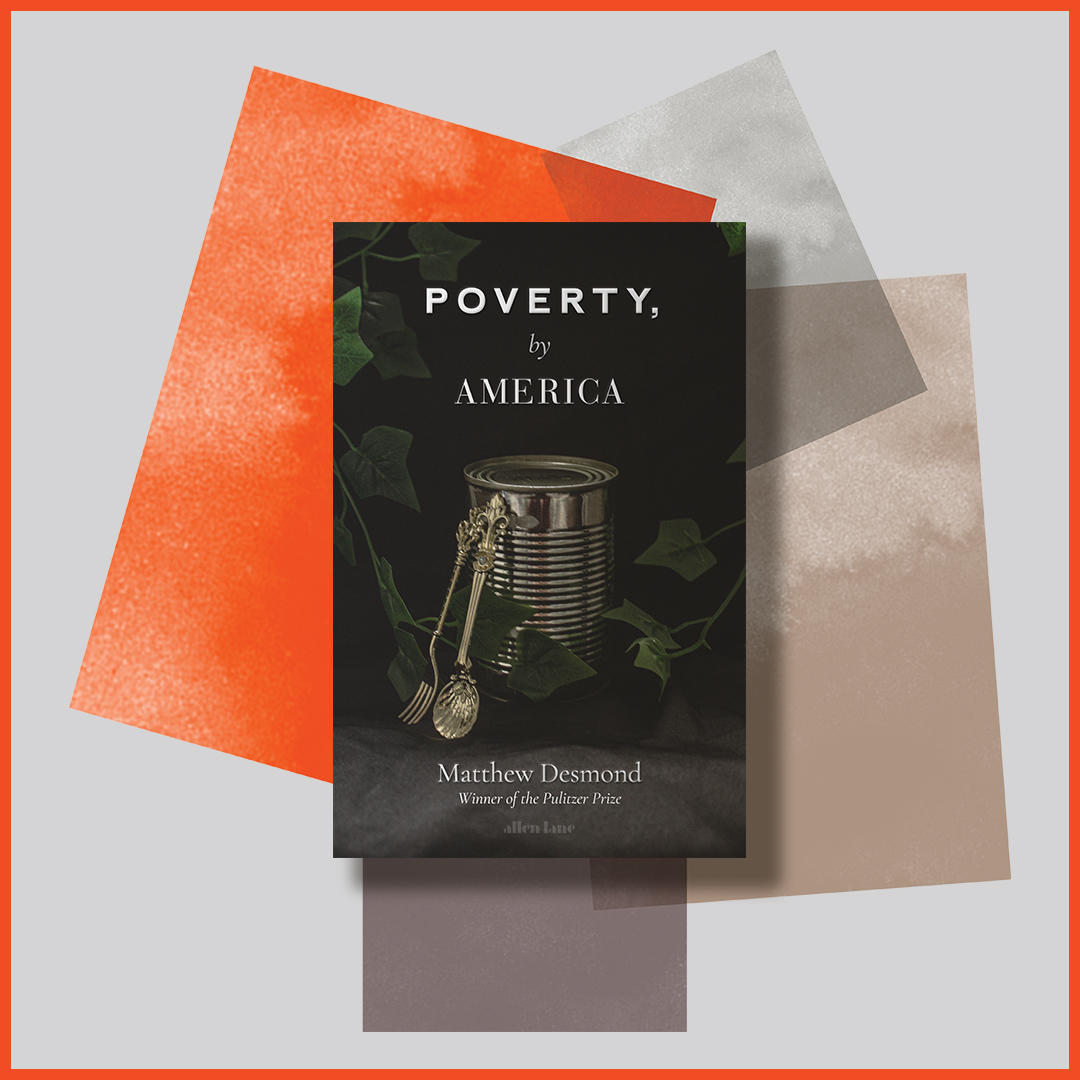

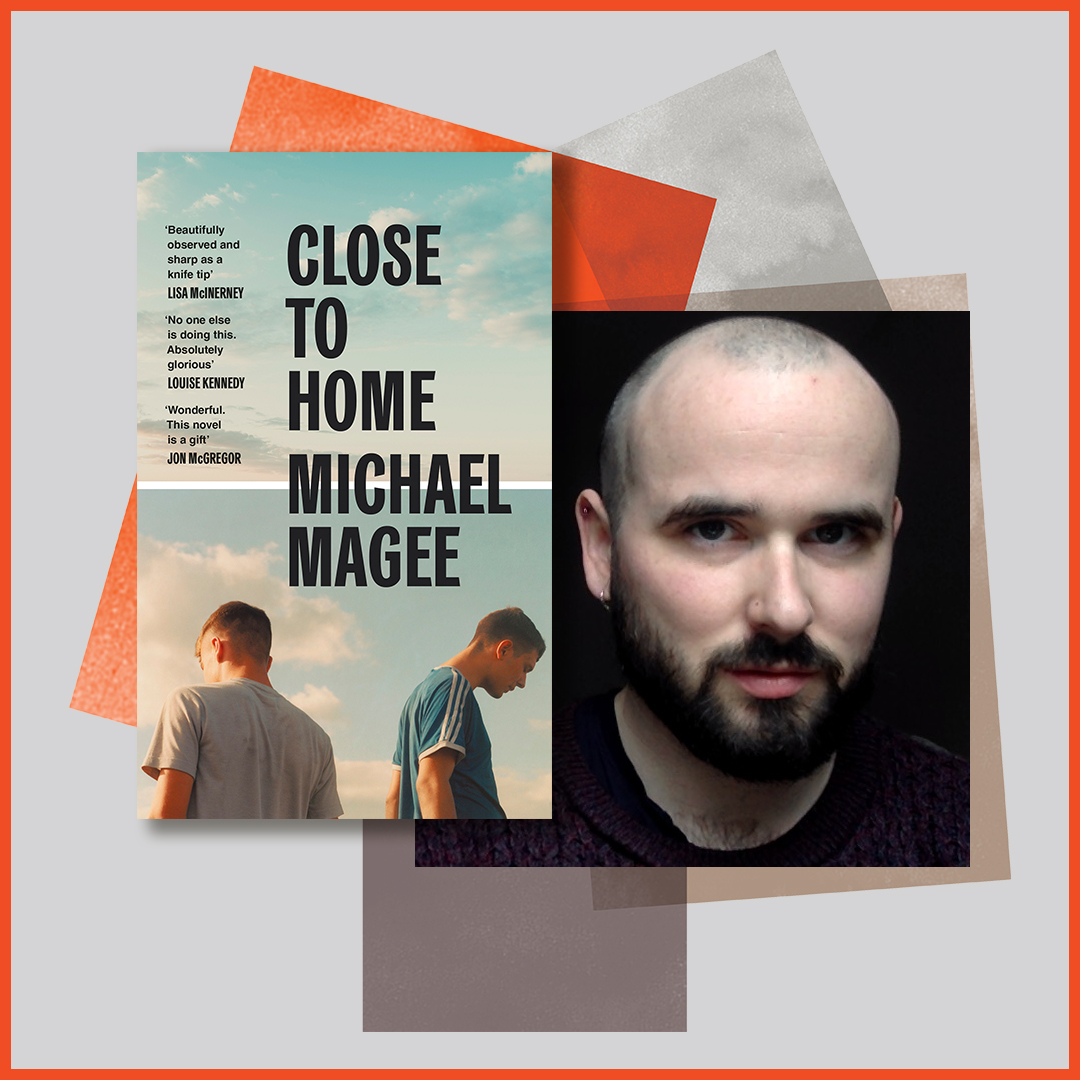

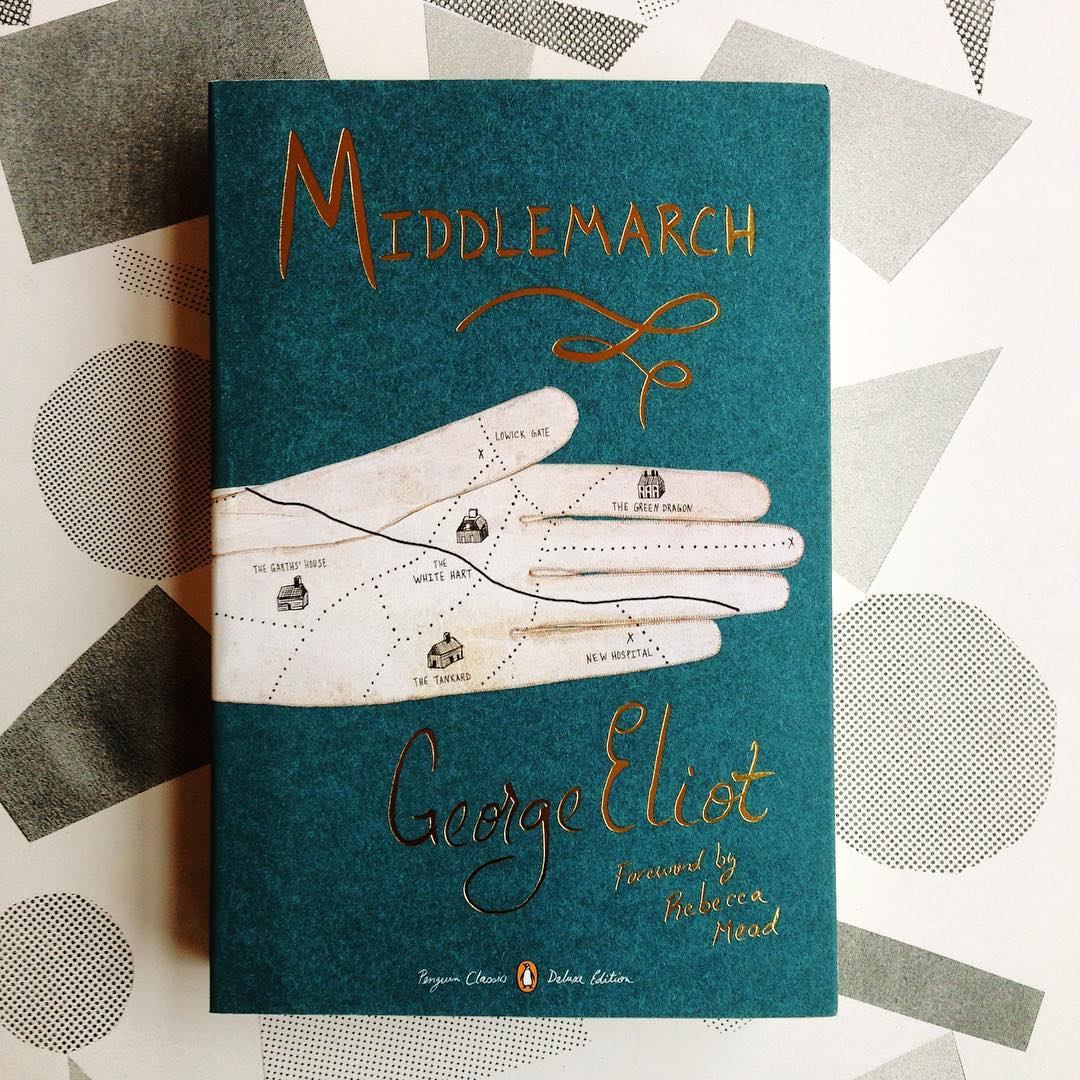

‘Middlemarch’ — George Eliot Anyone would at reading the classics if they owned the special editions on Libreria’s shelves. Here are 3 we think you’ll enjoy: The New Yorker’s Rebecca Mead describes how she emotionally evolves every time she reads George Eliot’s ‘Middlemarch’: ‘I have gone back to ‘Middlemarch’ every five years or so. In my judgmental twenties, I thought that Ladislaw, with his brown curls and his callow artistic dabbling, was not entirely deserving of Dorothea; by forty, I could better measure the appeal of his youthful energies and Byronic hairdressing, at least to his middle-aged creator, who was fifty-three when the book was published. My identification with Eliot’s heroine and my dismissal of her simpler sister was shaken when I became the besotted mother of a son. (To a friend, a professor of English literature, I giddily wrote, ‘All these years I’ve thought of myself as Dorothea, and now I’ve turned overnight into Celia.’) And as I grew older the unfolding of Dorothea’s life became less immediately poignant to me than the story of Lydgate, who at the start of the book has the bold aim to ‘make a link in the chain of discovery,’ but who, thanks to his own misguided marriage, becomes a society doctor known for a treatise on gout—’a disease which has a good deal of wealth on its side,’ in Eliot’s pointed observation.’ You can read the full article here: http://bit.ly/1y17154

-

‘Middlemarch’ — George Eliot

Anyone would #BeBetter at reading the classics if they owned the special editions on Libreria’s shelves. Here are 3 we think you’ll enjoy:

The New Yorker’s Rebecca Mead describes how she emotionally evolves every time she reads George Eliot’s ‘Middlemarch’: ‘I have gone back to ‘Middlemarch’ every five years or so. In my judgmental twenties, I thought that Ladislaw, with his brown curls and his callow artistic dabbling, was not entirely deserving of Dorothea; by forty, I could better measure the appeal of his youthful energies and Byronic hairdressing, at least to his middle-aged creator, who was fifty-three when the book was published. My identification with Eliot’s heroine and my dismissal of her simpler sister was shaken when I became the besotted mother of a son. (To a friend, a professor of English literature, I giddily wrote, ‘All these years I’ve thought of myself as Dorothea, and now I’ve turned overnight into Celia.’) And as I grew older the unfolding of Dorothea’s life became less immediately poignant to me than the story of Lydgate, who at the start of the book has the bold aim to ‘make a link in the chain of discovery,’ but who, thanks to his own misguided marriage, becomes a society doctor known for a treatise on gout—’a disease which has a good deal of wealth on its side,’ in Eliot’s pointed observation.’ You can read the full article here: http://bit.ly/1y17154

#librerialondon #libreriarecommends #libtriptych #newyorker #eliotvaustenIknowwhereImbetting

Libreria‘Middlemarch’ — George Eliot

Anyone would #BeBetter at reading the classics if they owned the special editions on Libreria’s shelves. Here are 3 we think you’ll enjoy:

The New Yorker’s Rebecca Mead describes how she emotionally evolves every time she reads George Eliot’s ‘Middlemarch’: ‘I have gone back to ‘Middlemarch’ every five years or so. In my judgmental twenties, I thought that Ladislaw, with his brown curls and his callow artistic dabbling, was not entirely deserving of Dorothea; by forty, I could better measure the appeal of his youthful energies and Byronic hairdressing, at least to his middle-aged creator, who was fifty-three when the book was published. My identification with Eliot’s heroine and my dismissal of her simpler sister was shaken when I became the besotted mother of a son. (To a friend, a professor of English literature, I giddily wrote, ‘All these years I’ve thought of myself as Dorothea, and now I’ve turned overnight into Celia.’) And as I grew older the unfolding of Dorothea’s life became less immediately poignant to me than the story of Lydgate, who at the start of the book has the bold aim to ‘make a link in the chain of discovery,’ but who, thanks to his own misguided marriage, becomes a society doctor known for a treatise on gout—’a disease which has a good deal of wealth on its side,’ in Eliot’s pointed observation.’ You can read the full article here: http://bit.ly/1y17154

#librerialondon #libreriarecommends #libtriptych #newyorker #eliotvaustenIknowwhereImbetting